Trading Cocoa through Contracts for Difference

Before diving into the specifics of cocoa, a solid understanding of how CFDs work and how they differ from buying futures contracts is required. These are some of the key features of trading cocoa through a CFD:

- A CFD is a cash-settled derivative. This means you never physically buy, sell, or take delivery of cocoa. You are speculating on a contract that is made to track the prices of cocoa futures in major markets. Using a CFD thus allows you to speculate on cocoa prices without ever having to worry about rolling over a futures contract or undertaking physical delivery.

- CFDs allow you to use leverage, enabling you to use your capital more effectively. Using leverage wisely allows you to hold multiple positions at a time without tying up all your capital in just one asset. It also allows you to size up positions and potentially make significant profit from intraday swings that would otherwise achieve only a small percentage gain. Leverage is a tool; when used wisely, it can amplify potential returns, but if used without understanding, it can also increase the size of losses.

- Unlike a physical investment, holding a CFD position past the daily market close typically incurs an overnight financing charge (or 'swap fee'). This cost makes holding positions for extended periods less profitable. Therefore, the strategies discussed below are suited more for short to medium-term trades instead of longer-term investments.

Understanding Cocoa Production

In any asset class, it makes sense to specialize in one or a few markets, to truly understand every single driver that goes into price, and gain unique insights from mastering the fundamentals of this asset class. This is especially true for soft commodities like cocoa, where prices are influenced by highly specific factors such as supply threats, weather patterns, geographic concentration, and geopolitical risks.

Before we discuss how to trade cocoa, let's explore its unique production process.

Harvesting cycles

Cocoa typically has two harvest periods. The first is the Main Crop, which runs from October to March and provides the majority of the global supply. The second is the Mid-Crop, a smaller harvest that occurs between May and August. The Mid-Crop is critical because it bridges the supply gap until the next main harvest.

Unfavorable weather during the Mid-Crop can have a significant impact on prices, as it could signal a tight supply until the next major harvest begins in October.

Geographical concentration and Climate

The cocoa market is highly concentrated, with approximately 60% of the world's supply originating from just four West African nations: the Ivory Coast, Ghana, Cameroon, and Nigeria. As a result, weather conditions in West Africa are a crucial factor to monitor, much like you would track U.S. economic policy when trading Forex or indices.

This geographical concentration is a direct result of the plant's demanding climate requirements. Cocoa thrives in a consistently warm, humid climate with plenty of shade. This is why it is often grown in tropical rainforests, within 10 degrees of the equator. The ideal temperature range is 20–30°C (68–86°F), and the plant requires high air moisture. To protect it from wind and direct sunlight, cocoa trees are often planted under larger trees, a technique known as sombramiento.

The plant is highly sensitive to its environment; temperatures below 10°C (50°F) can quickly damage or kill it. As a result, cocoa production is primarily limited to three distinct regions:

- South America (primarily Ecuador and Brazil)

- West Africa

- Southeast Asia (concentrated in Indonesia)

While other regions do produce cocoa, their output is minimal, so a trader's focus should remain on these three key areas.

Cocoa: The Supply Side

Now that we’ve got an overview of where cocoa beans are grown and what requirements they have, we can go further into the specific fundamental drivers that determine price from the supply side.

Diseases and viruses

Diseases can have a devastating impact on the cocoa supply. For example, the cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus Disease (CSSVD), transmitted by mealybugs, has been responsible for significant harvest losses of as much as 50% in Ghana alone. Other diseases, such as Black Pod, can halve the total output of a cocoa farm.

Mitigating these diseases is very expensive and often requires that new trees be planted. A major issue is that cocoa trees require a minimum of three years to bear fruit and only reach their optimal productive potential after five to seven years. This long lead time means that a disease outbreak can have a durable impact on the supply chain.

Ageing Infrastructure

Cocoa production naturally declines after a tree reaches 18 to 20 years, forcing farmers to anticipate future demand far in advance, as it takes multiple years before new trees can start to bear fruit. However, these farmers earn very little from their production, making it impossible for them to make the necessary investments to keep up with (future) demand.

This is largely because they work with fixed prices. Normally, an increase in prices would see a relatively large part of that extra profit go towards the farmers (as chocolate producers would transfer the higher cost to the end customer), which would have a stabilizing future impact as it would put the farmers in the position to intensively plant more trees, helping to stabilize future prices through increased supply.

However, the current situation leads to a spiral where not enough new trees are being planted, while the yield of the old trees continues to decline. This makes future supply shocks more likely.

The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) as a Trade Barrier

This regulation, effective since December 2024, requires that cocoa production be deforestation-free, meaning that only land can be used that has not been deforested after December 31, 2020.

This regulation is a significant compliance effort, one which will drive up expenses for the West-African farms, whose major export region is the EU.

Climate change as a durable supply disruptor

As a commodity that requires a very specific climate to thrive, cocoa is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The droughts in West Africa during 2024 contributed to prices nearly tripling in a matter of months. As long-term weather patterns become increasingly unpredictable, this will create opportunities for traders who closely analyze the weather reports.

Cocoa: A Demand-Driven Commodity

Cocoa differs from most other soft commodities in that it is more of a luxury product, leading to a higher price sensitivity. This means that when we see big price increases that have to be paid by the consumer, we can expect noticeable decreases in consumption, compared to other soft commodities, where demand would remain mostly flat.

Because of this, it’s important to not only look at the supply-side, but also the demand-side. This is where the quarterly “Grind Report” comes in. This report is published by a distinct European, North American, and Asian Cocoa Association, detailing the bean usage by big companies like Barry-Callebaut, Mondelez, and Lindt, among others. These reports hold a very high significance for Cocoa prices and create short-term volatility.

For example, the most recent report showed a significant year-over-year decrease in demand across all three regions, although most notable in Asia:

| Region/Association |

Q2 2025 Grindings in Tonnes |

Year-over-Year Change |

| Europe (ECA) |

331,762 |

-7.2% |

| Asia (CAA) |

176,644 |

-16.28% |

| North America (NCA) |

101,865 |

-2.78% |

Market Participants: Who Drives Prices?

As we discussed in our guide to trading soft commodities, there are three main participants in every financial market:

- Hedgers: Companies that minimize their business risk by opening positions in the opposite direction of their business exposure

- Non-commercials: Hedge funds and mutual funds

- Non-reportables: Retail traders

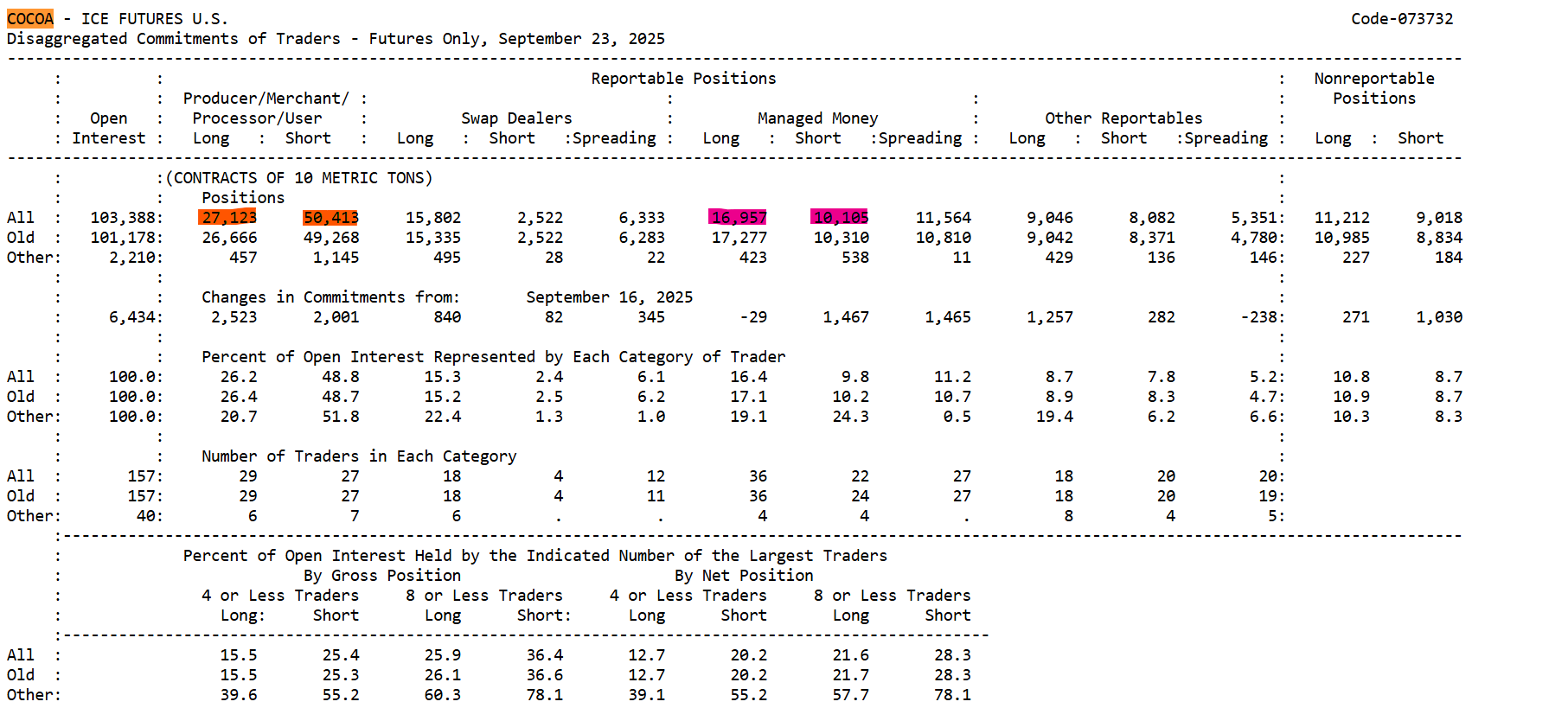

We can then analyze their open positions through the Commitment of Traders (COT) report, which discloses futures positions in U.S. markets. As we noted earlier, CFDs are based on the prices of futures contracts, so analysing futures markets when you’re trading CFDs is still very much relevant. This is a screenshot from the latest COT report for cocoa:

Open interest shows us the grand total of current open positions (not to be confused with volume).

From this report, we can learn that hedgers (Producer/Merchant/Processor/User) are by far the biggest participant, with 27.123 contracts worth of long positions and 50.413 contracts worth of short positions. The fact that the short positions are over twice as big indicates that a lot of these producers are hedging the risk of the price going down, which means that these are positions opened by those selling raw cocoa, i.e., farmers.

Interestingly enough, chocolate producers don’t hold nearly as many open positions long positions to offset upside risk, possibly indicating that they are currently expecting a relatively low risk of significant price increases.

Managed Money is another interesting category. This shows us that hedge funds and mutual funds are collectively net long on the cocoa market, which can be interpreted in multiple ways:

- Price is more likely to go up, as institutional players with significant research resources are betting on this.

- Long positions from these entities are vulnerable to any news that shows improvements in the future supply, as they will unwind their positions if their original bullish thesis weakens.

While this may seem confusing, there is no single way to analyze market participant behavior through the COT report. It all comes down to your specific trading setup. The COT report is not enough to create a setup on its own; it serves more as a way of confirming your fundamental thesis and observing how participants are behaving both in comparison to each other and through time.

The key to analyzing these positions is to always consider what each category is trying to achieve. For example, when hedgers are opening positions, it's because their business has negative exposure in the direction of the contract (long positions are opened because they want to diminish the risk of rising prices, indicating that they need to buy cocoa).

Conclusion

The cocoa market is fundamentally unique and structurally challenged. Supply is constrained by long-term risks, including diseases, old infrastructure, regulatory risks, and climate change. While demand is sensitive to price changes, these shifts have been too small to consistently limit price behavior. This dynamic creates a market that is likely to see significant volatility in the future, offering substantial opportunities for traders who are prepared to conduct the necessary analysis of all the underlying factors.

Ready to put your newfound knowledge of cocoa to the test?