Cotton, often referred to as "white gold," is far from a simple asset to trade. Its price behaviour is defined by a complex interaction between agricultural science, supply chain logistics, and global macroeconomic policy. For retail traders looking to enter this dynamic market, a deep understanding of the core fundamental drivers is essential.

This article provides an in-depth guide to the fundamental factors and key reports you can use to develop informed trading strategies for cotton.

Trading Cotton via Contracts for Difference (CFDs)

Before diving into the specifics of cotton, a solid understanding of how CFDs work and how they differ from buying futures contracts is required. These are some of the key features of trading cotton through a CFD:

- A CFD is a cash-settled derivative. This means you never physically buy, sell, or take delivery of cotton. You are speculating on a contract that is made to track the prices of cotton futures in major markets. Using CFDs thus allows you to speculate on cotton prices without ever having to worry about rolling over a futures contract or undertaking physical delivery.

- CFDs allow you to use leverage, enabling you to use your capital more effectively. Using leverage wisely allows you to hold multiple positions at a time without tying up all your capital in just one asset. It also allows you to size up positions and potentially make significant profit from intraday swings that would otherwise achieve only a small percentage gain. Leverage is a tool; when used wisely, it can increase potential returns, but if used without understanding, it will amplify the size of losses.

- Unlike a physical investment, holding a CFD position past the daily market close typically incurs an overnight financing charge (or 'swap fee'). This cost makes holding positions for long periods less profitable. Therefore, the strategies discussed below are suited more for short to medium-term trades instead of longer-term investments.

Fundamentals: The Supply-Side Dynamics

To profitably trade cotton, traders must understand the agricultural and geopolitical factors that shape global supply.

Cotton Cultivation: From Seed to Bale

First, a quick biology lesson. Cotton thrives in warm weather and requires a long, frost-free growing season to mature. It gets planted as early as possible in the spring so that it has as much time as possible to mature, as its growing season is longer than most crops.

The biggest cotton producers are China, India, Brazil, and the U.S.. Together, these four countries produce 70-75% of the global output. A key structural factor is that much of this production (excluding the U.S.) originates from small, family-owned holdings. This can result in production decisions being driven more by local economic needs than by immediate global price signals, often slowing the supply curve's reaction to price spikes and contributing to market volatility.

Pests: A Major Production Challenge

Insect pest management represents the single highest variable cost when producing cotton. Key pests include:

- The cotton bollworm

- Plant bugs

- Stink bugs

- Aphids

- Thrips

The industry has adopted genetically modified (GM) cotton to mitigate these challenges, which significantly reduces the need for certain insecticides. However, this shift can inadvertently benefit other pest varieties that the GM cotton is not engineered to resist.

The Sustainability Mandate

There is a growing demand from major global fashion and textile brands for organic and traceable cotton. Compliance with these high-standard traceability mandates requires rigorous monitoring throughout the supply chain and leads to significantly higher production costs compared to non-compliant, generic cotton. This growing demand creates a persistent and increasing price spread between "sustainable" and generic cotton varieties.

Geopolitical Impact: The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA)

Due to concerns about the use of forced labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China, the U.S. has banned the export of all goods produced inside this region to the United States. This has a profound impact on cotton prices, as 90% of China’s cotton production takes place inside this region.

As a result, the Chinese market is shielded from a major export partner. This leads to overall rather low Chinese cotton exports, with most of the produced cotton being used domestically. It is thus possible to see price increases in cotton prices (which are based on ICE US futures) while there’s plenty of supply inside the Chinese market.

The WASDE report: Gauging Global Supply and Demand

The World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report, released monthly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), is arguably the single most important monthly publication for agricultural commodities. It provides detailed forecasts on global production, consumption, trade, and prices for cotton. Traders closely monitor the WASDE for any revisions to these forecasts, as deviations from market expectations can lead to short-term volatility.

In this instance, the price shot up by almost 2% over the following two hours. While 2% might seem small, we have to take into consideration that the daily average true range at that point was just a 2.3% price difference. Surprises in the WASDE report can thus lead to sudden price increases.

Cotton: A Demand-Driven Commodity

In our article giving an overview of how to trade soft commodities as a whole, we noted that soft commodities are mostly supply-driven. Since assets like wheat, corn, soybeans, and others are essential purchases, demand stays relatively flat irrespective of price increases. But, because apparel and textiles are often viewed as non-essential purchases, global recessions lead directly to lower demand for cotton.

For instance, during the COVID-19 shock, cotton mill output dropped 15% year-over-year, which was a reduction unseen during the previous decade. Furthermore, studies have shown that periods of extreme volatility in cotton markets are primarily correlated with macroeconomic instability, and not agricultural disasters. From this, we can conclude that broad financial health is the primary driver of cotton.

The Continued Rise of Cotton Substitutes

Cotton exists in a perpetual competitive struggle against artificially made fibers, a contest which it is currently losing. Cotton accounts for only 19% of the world’s total textile fiber market. By contrast, synthetic polyester dominates, claiming 59% of total fiber production.

Polyester production continues to grow, demonstrating an annual growth of 9.8%. This structural asymmetry in production capacity is a long-term bearish bias for cotton prices.

Oil Price as a Leading Indicator

Artificially made fibers, such as polyester, are made from oil. Therefore, higher crude oil prices translate into higher input costs for polyester and other cotton substitutes. This price increase makes cotton a more competitive viable alternative, potentially increasing demand for it and supporting its price.

Oil prices thus serve as a leading indicator: big price increases should be reflected in increased demand for cotton. However, this is a delicate balance, as any resulting appreciation in cotton prices will eventually hit a threshold where textile mills substitute back again to synthetic materials, creating a self-balancing force in the markets.

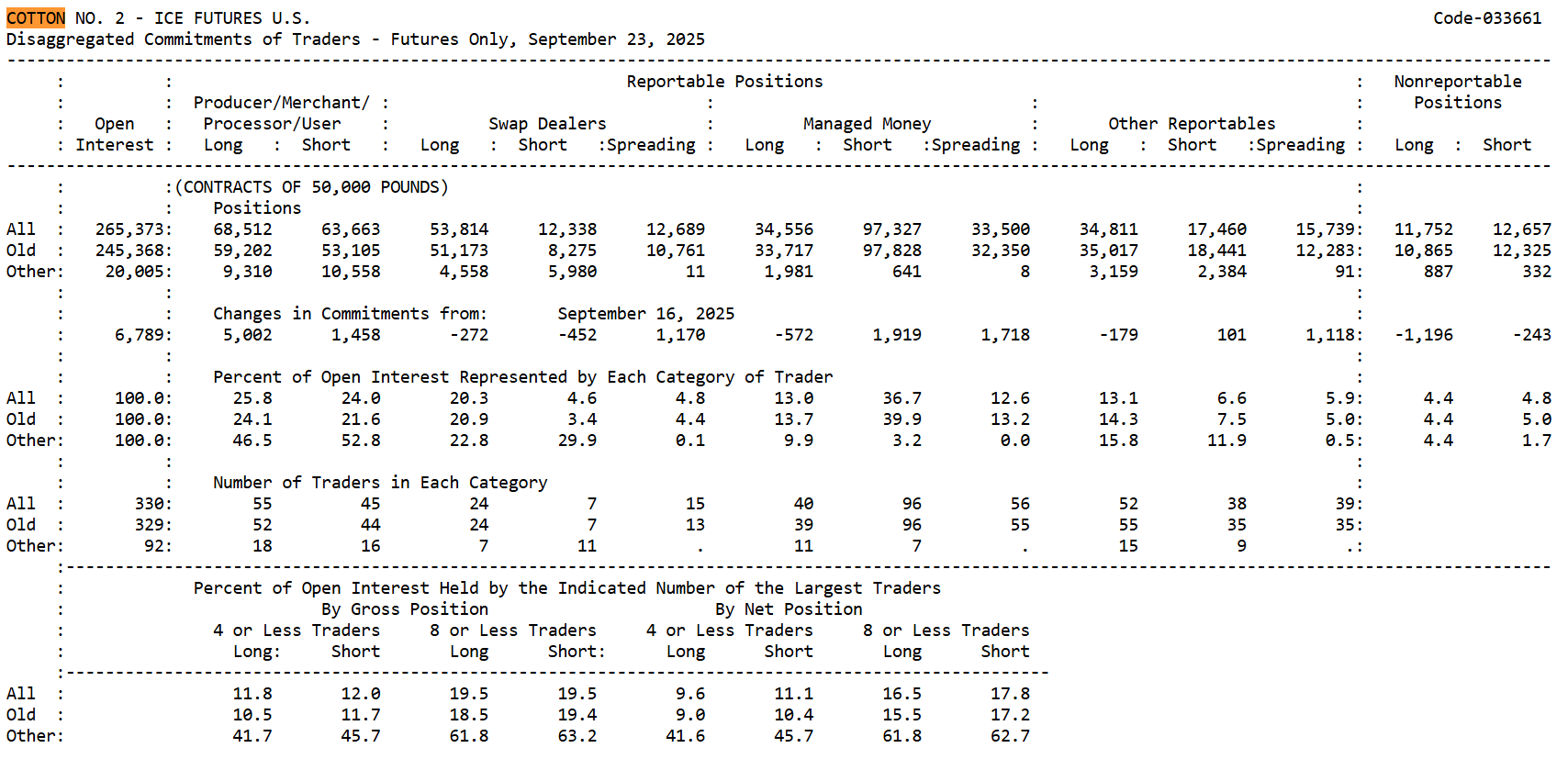

The Commitments of Traders Report: Analyzing Market Participants

The Commitments of Traders (CoT) report offers invaluable insight into the positioning of institutional market participants. This report is most effectively used as a confirmation for a pre-existing technical or fundamental trade idea, rather than a standalone trading signal.

Commercial traders are often regarded as the "smart money" due to their direct involvement in the physical market. Their positioning reveals their forward market expectations: when Commercials accumulate extreme net short positions, it implies they believe current prices are high and anticipate needing to sell inventory. Conversely, when they move toward extreme net long positioning (a low hedge ratio), it often indicates an expectation of rising prices as they secure future consumption or production needs.

Managed Money (speculators), however, often represent the crowded trade; their extreme net long positioning frequently serves as a high-probability contrarian short signal, particularly when combined with overbought technical market indicators.

The CoT report, however, should not be viewed statically. It provides the most value when observing the data throughout time, in combination with monitoring price. By doing this, patterns will emerge. You might learn that when commercials are slowly expanding their net positions week by week (opening more longs), the price can create a sustained uptrend.

Conclusion

The cotton market presents a highly complex profile, defined by its blend of agricultural seasonality, geopolitical supply constraints, and highly elastic, macroeconomically sensitive demand. Profitable traders employ and keep these fundamental insights into consideration and combine them with unique, in-depth analysis to identify high Expected Value (EV) setups.

Ready to trade Cotton CFDs?